My son, Francois, and I went to New York for an anniversary party of Per Se, the elegant restaurant of Thomas Keller that opened 20 years ago. It’s located on the fourth floor in what used to be called the Time-Warner building that overlooks Columbus Circle and a corner of Central Park. Only New York or London, I think, could have a building in which the 78th floor penthouse was sold in 2015 by a Russian Oligarch for $51 million.

When we arrived, the restaurant was already completely filled with guests who, like us, were handed a glass of champagne as we entered, and then left to walk around, greet others we knew, and taste food.

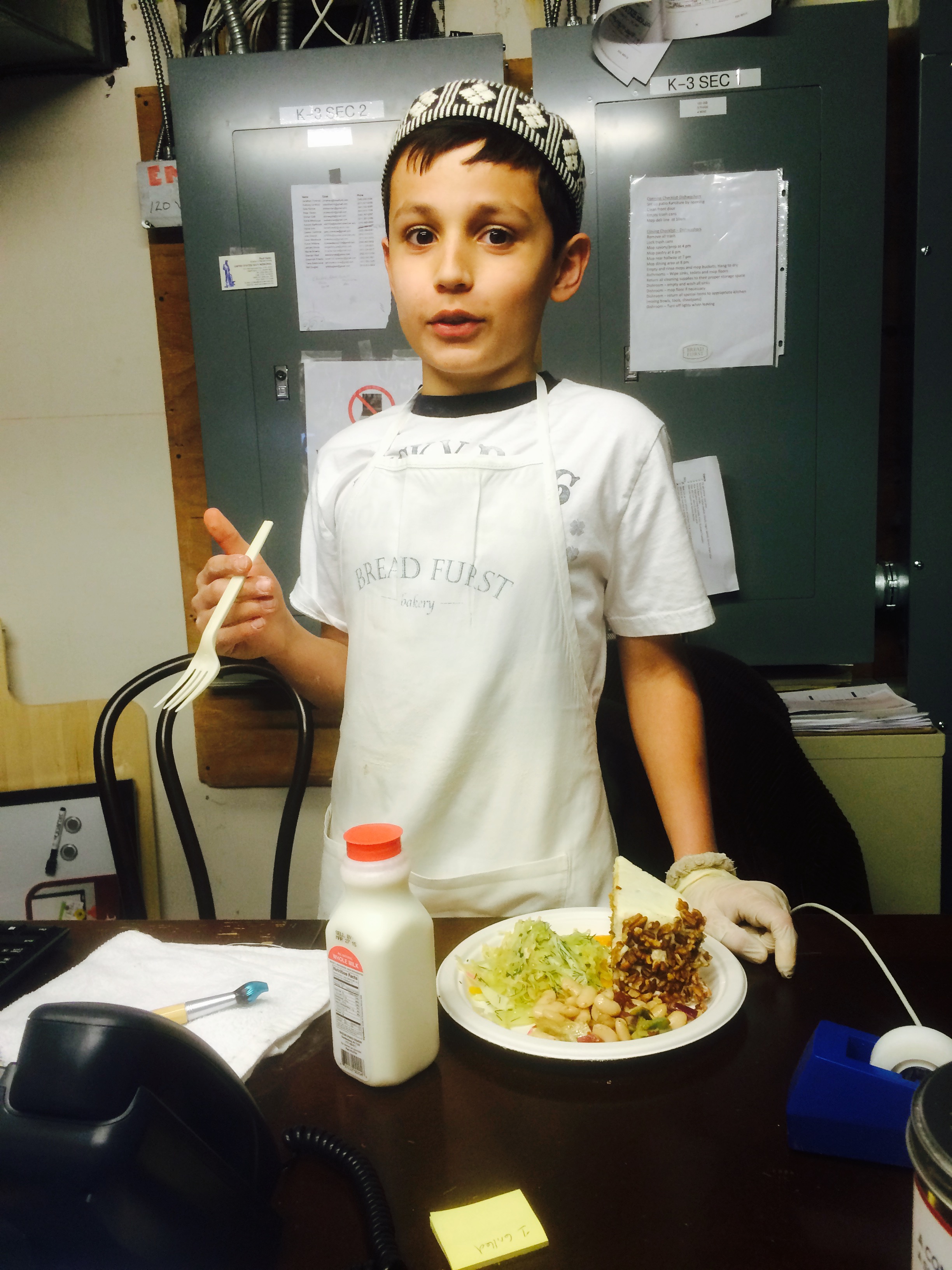

I don’t like eating that way – nibbles of random food – but Francois doesn’t feel the same way and tasted until he had used all of his prodigious store of taste buds. For me, the visit was purely evocative.

My memories of Per Se’s opening 20 years ago are vivid. On a cold spring day, I toured the building with its developer and Thomas when it was still being constructed, admiring the fancy shops that hadn’t yet opened, not fully appreciating the magnitude of the enterprise, cowed by the opening of the Whole Foods in the basement that was grossing a million dollars a week even though it hadn’t yet worked out a customer service that allowed shoppers to leave the store before their lettuce had wilted.

There is a chapter in my book about Thomas Keller and the opening of Bouchon Bakery in Yountville. I was the bakery’s consultant in 2004, and traveled from Yountville for the opening of the bakery there, to Las Vegas for the opening of the bakery inside the Venetian Hotel, and then to New York for the opening of that branch of Bouchon Bakery inside Per Se.

I had met Thomas in 1995 when I was the opening baking instructor at Greystone, the West Coast branch of the Culinary Institute of America, known as the CIA, but I never dared to call it that as I had previous experiences in another CIA that most of us in Washington know.

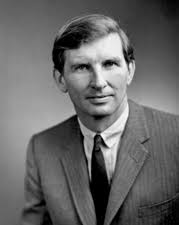

In the late Eighties Thomas had a restaurant in New York, a critical success and a commercial failure, and then a restaurant in Los Angeles, a critical success and a commercial failure. After those disappointments, he scraped together enough money to buy The French Laundry from the good-hearted couple who wanted him to have it. He had opened it in 1994, and by 1995, although Thomas was receiving a lot of attention from his colleagues, the restaurant was still so new that it had not attracted much press attention.

Jean Louis Palladin, my friend in Washington, too was beginning a new life, moving from Washington to Las Vegas. Even the building known as Greystone, built as the Christian Brothers Winery, was beginning a new life as a culinary school.

All the owners of vineyards in Napa and Sonoma Valley were invited to attend a party put on by the new Las Vegas hotel in which Jean Louis’ restaurant was to be located. But they didn’t come.

Why should they have come? What should Napa Valley winemakers have cared about a new restaurant in a new Las Vegas casino? They were California wine makers. They certainly weren’t attracted by the wine the Rio was to show off – they had their own. And so the cavernous Barrel Room of Greystone was nearly empty.

But we were there, Greystone faculty, Napa Valley chefs and a few other chefs – Roberto Donna from Washington, Eric Ripert from New York, Jean Joho from Chicago, friends of Jean Louis who had flown in, and some Napa Valley chefs, all standing in little booths around the great room, ready to serve food to the guests who didn’t come.

None of the chefs complained. We enjoyed seeing each other and were looking forward to being together that evening. Besides we didn’t care about the winemakers; we had gone there to honor the new life step for Jean Louis who, because he continuously celebrated the success of others, because of his generosity to other chefs, had brought us to Napa Valley which wasn’t – and isn’t – such a bad place to be even if the winemakers didn’t come.

A bizarre little man wandered by, wearing a black suit with a jacket that flared and black tie, pushing up his horn-rimmed glasses with his middle finger. “You may have read that I had the great honor last week,” he told me sententiously and without my having asked a question, “of presenting the Baron Rothschild with a check for one million dollars for a perfect vertical collection of Chateau Lafite, his great wine.”

Indeed, in the front of the huge room were high pedestals on which were resting Imperials of 1982 and 1961 Lafitte. I took another large glassful of the greatly inferior wine being served to us.

“When are you going to open those,” I asked, pointing to the huge bottles at the front of the room.

“Ha, ha, ha, very funny,” he turned away.

I was bored. The room was practically empty. I had baked breads and was standing at a table on which I had piled my loaves. The slices I had cut were drying in baskets at the front of the table. I was going to meet Jean Louis and the others later and thought I might move our closing time up a little. Even Jean Louis, being honored, looked bored.

I wandered away from my table to look at what the other chefs were serving; and at the very back of the room below vast windows at the front of the building, I came upon Thomas Keller standing in a little booth behind perforated trays of his not-yet-famous little cornets with salmon tartar, crème fraiche, and caviar peeking from trays that looked like painters’ palettes. I had never met him.

“What are you doing here,” I asked him.

“I was wondering the same thing,” he said.

Francois found me at the celebration, thrusting his caviar at me. I wandered over to the table that held it. Tin after tin of it. I followed him to the truffle table where a server was shaving obscene quantities of black truffles over pasta. Oysters, snapper ceviche, beef Wellington, a great platter of cheeses, charcuterie, a Wagu “corn dog,” Hobbs bacon and quail eggs.

I wanted to see what has happened to the bakery that I had helped open. The corridor back through the kitchens was filled with guests eating chocolates being made in the chocolate room and pastries made in the pastry kitchen.

A lot had changed back there. I didn’t recognize the oven being used to make bread; it was an oven that replaced the one I had used.

The evening went on. The noise was too loud for an old man with little hearing. Thomas was dressed in whites so that guests could see him. Laura was dressed beautifully – she always is. Francois and I wore jackets and ties; other guests were dressed in wild outfits. The celebration was fabulous.

Thomas is a remarkable man of great talent, one of whose qualities is an equally endless generosity. No one I know other than Thomas would empty a fabulously successful restaurant for an evening, fill it with three dozen cooking stations making food to give away to all those he invited to treat.

d not refuse a customer. When Jean Louis did just that, Shoffner called the police.

d not refuse a customer. When Jean Louis did just that, Shoffner called the police.

It’s all so easy. Sometimes I have to correct foods I make by adding more garlic or by thinning with V-8 or by thickening with a little tomato paste. But there are very few rules.

It’s all so easy. Sometimes I have to correct foods I make by adding more garlic or by thinning with V-8 or by thickening with a little tomato paste. But there are very few rules.